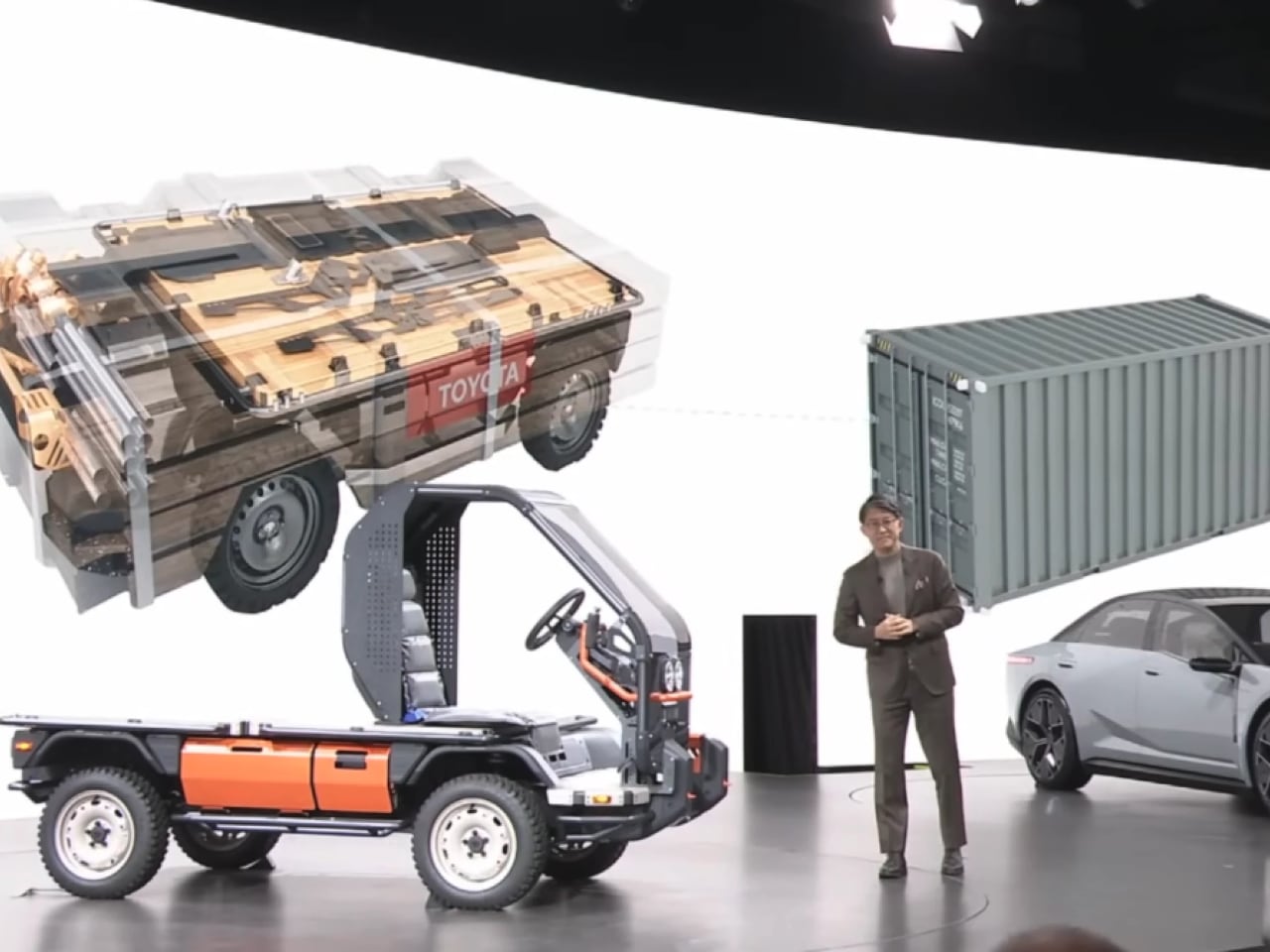

The Toyota IMV Origin arrived at the 2025 Japan Mobility Show stripped down to almost nothing, and that was entirely intentional. Where conventional vehicle concepts arrive polished and production ready, the IMV Origin presented itself as a skeletal flatbed with an open air single seat cab, barely recognizable as a truck at all. Toyota’s approach here inverts the typical automaker logic: instead of delivering a finished product, the company ships a foundation, a canvas, a system of parts that local communities complete on their own terms. The concept draws from Toyota’s long running Innovative International Multi-purpose Vehicle platform, which already emphasizes flexibility and regional adaptation. Revealed during the same press conference that showcased flashier vehicles and premium brand expansions, the IMV Origin quietly proposed something more radical: a vehicle that gains value and identity only after it leaves the factory.

Designer: Toyota

Koji Sato, Toyota’s president and CEO, described the underlying philosophy in direct terms during the Japan Mobility Show presentation. The first idea, he explained, was to ship the vehicle unfinished, allowing the local people who receive it to assemble and complete it themselves. The second idea extended that premise further: customers would define the vehicle on their own terms even after assembly, choosing whether it carries people or cargo, boxes or something else entirely. Toyota builds the base, and from there each user completes the vehicle to fit specific needs. This framing positions the IMV Origin not as a truck but as a design system, a physical framework for distributed creativity that shifts final authorship away from the factory floor and into the hands of communities scattered across emerging markets.

Designing a Vehicle That Arrives Unfinished

That philosophy becomes visible in the physical form itself. The Toyota IMV Origin reads less like a finished vehicle and more like a piece of industrial furniture waiting for context. A flat chassis defines the primary surface, interrupted only by a minimal open cab structure designed for a single occupant. There is no enclosed cabin, no rear bed walls, no cargo box, no secondary seating. The silhouette suggests a factory cart or a stripped down work platform rather than anything destined for public roads. This visual starkness serves a functional purpose: every absent panel, every missing enclosure represents space for local fabrication and adaptation.

Toyota’s shipping model borrows imagery from flat pack furniture, a comparison Sato made explicit during the Japan Mobility Show press conference. The idea is that the IMV Origin ships as a crate of assemble yourself components, packed efficiently enough to slide into a standard shipping container. Buyers receive the rolling chassis, the cab frame, the essential mechanical systems, and presumably a set of instructions and basic tools. Assembly happens on arrival, requiring some combination of included hardware and locally sourced equipment. The furniture analogy carries weight here: just as a bookshelf arrives as panels and fasteners awaiting configuration, the IMV Origin arrives as a vehicle skeleton awaiting completion. This approach compresses shipping volume, reduces transport costs, and distributes final assembly labor to regions where that labor already exists and seeks work.

The open cab structure reveals how Toyota communicates modularity through form. By leaving the driver’s area exposed rather than enclosed, the company signals that even this fundamental zone remains open to interpretation. A buyer might add a windscreen, side panels, a full roof, or leave the cab skeletal for maximum airflow in hot climates. The single seat default suggests solo commercial use, but the surrounding space invites expansion to two seats or more. Every surface of the IMV Origin exists as a potential attachment point, a mounting location, a starting place for fabrication. The form does not dictate function; it invites negotiation.

The visual openness of the chassis functions almost like an instruction diagram for local builders. Exposed rails, visible mounting surfaces, and unobstructed structural geometry signal exactly where modules can attach. A fabricator examining the modular truck concept does not need a manual to understand where a cargo box might bolt or where a cab enclosure could fasten. The stripped form communicates its own logic, revealing load paths and connection points through the simple act of leaving them visible. Toyota’s decision to ship the vehicle unfinished becomes, in this light, a form of design communication: the geometry itself teaches the user how to complete it.

How Local Assembly Shapes Everyday Use

The design logic extends directly into how people actually use the vehicle. The user experience of the Toyota IMV Origin begins not with driving but with building. A farmer in rural Africa might receive the crated components, unpack them with neighbors, and spend a day or a week assembling the base vehicle. The process itself becomes a form of ownership, a hands on introduction to every mechanical connection and structural joint. By the time the owner starts the engine for the first time, they already understand how the vehicle fits together, which fasteners hold the cab frame, where the chassis accepts additional load. This knowledge carries forward into repair and modification, lowering the barrier to maintenance and customization.

Toyota showed several example configurations at the Japan Mobility Show press conference, including a produce delivery truck with a tall cargo box and a logging truck with open stake sides. These illustrations suggest the range of possibilities without defining limits. A community workshop in a small agricultural town might fabricate a cargo bed with fold down sides, bolted directly to the exposed chassis rails, for transporting harvested crops over uneven dirt roads. Another shop could build a modular fire response carrier, using the visible mounting surfaces to secure water tanks and equipment racks for rapid deployment across scattered villages. A regional upfitter with welding equipment might create a lightweight camper module, fastening a sleeping platform and basic storage to the flatbed’s open connection points, transforming the IMV Origin into a mobile shelter for seasonal workers or traveling repair crews. Each scenario draws on locally available materials, locally developed skills, and locally understood needs.

The modularity extends beyond the initial build, allowing role changes across seasons without requiring a new vehicle purchase. A single IMV Origin might serve as a produce hauler during harvest season, then swap its cargo box for a flatbed configuration to transport building materials during construction months, then add a canopy and seating for passenger transport during community events. This flexibility mirrors the way rural economies actually function, where a single asset often serves multiple purposes across different seasons and circumstances. The design anticipates that reality rather than ignoring it.

Sustainability Through Local Fabrication and Modular Updates

These same structural choices carry environmental consequences that compound over time. Shipping a compact crate of components rather than a fully assembled vehicle reduces the volumetric footprint of each unit in transit. Fewer shipping containers, smaller cargo holds, and more efficient packing translate directly into lower fuel consumption and reduced emissions during international transport. The sustainability benefit begins before the vehicle ever reaches its destination, embedded in the logistics strategy rather than added as an afterthought.

Local assembly creates additional environmental value by distributing expertise and reducing dependence on distant supply chains. When communities build and maintain their own vehicles, they develop skills that support long term durability. A locally fabricated cargo box can be repaired with locally sourced materials when it sustains damage. A cab enclosure built by a regional shop can be modified or replaced without importing new parts from distant factories. In regions where replacement parts are expensive or difficult to obtain, this local capability becomes a practical necessity as much as an environmental virtue.

The IMV Origin’s intentional incompleteness encourages a culture of repair over replacement, extending the useful life of the base platform and reducing the frequency of full vehicle turnover. Rather than discarding an entire vehicle when needs change, owners upgrade or swap individual components. A farmer who expands operations might add a second seat to the cab rather than purchasing a larger truck. A delivery service that shifts from dry goods to refrigerated cargo might install an insulated box module rather than acquiring a purpose built refrigerated vehicle. Each modular intervention preserves the embedded energy and material value of the existing platform while adapting it to new requirements.

Durability emerges not from overengineering but from accessibility: the vehicle lasts longer because owners can fix it, adapt it, and extend its usefulness without specialized tools or imported components. Toyota’s willingness to leave the product unfinished becomes, paradoxically, a strategy for longevity.

Where the IMV Origin Fits in Toyota’s Modular Platform Roadmap

This approach did not emerge in isolation. The Toyota IMV Origin sits at the most stripped down end of a spectrum that already includes the IMV 0 concept and the production Hilux Champ. The IMV 0, revealed in 2022, offered a simplified small truck platform with strong modularity but still arrived as a recognizable vehicle. The Hilux Champ, which debuted in Thailand in 2023, translated that modularity into a production reality, spawning mini motorhomes, delivery trucks, food trucks, and overland campers through partnerships with regional body shops. Indonesia’s version, the Hilux Rangga, inspired a design competition that produced fire trucks, police tactical vehicles, agricultural transporters, and recreational campers. The IMV Origin steps further back along this trajectory, offering even less finished hardware and even more open ended potential.

This positioning reveals something about Toyota’s strategy for global mobility within the broader IMV platform family. Rather than designing a single truck and adapting it for different markets through factory options, the company designs a platform that markets adapt themselves. The factory provides the mechanical core, the structural integrity, the safety critical systems. Everything else becomes a canvas for regional creativity. This approach acknowledges that Toyota cannot anticipate every use case, cannot understand every local need, cannot predict how a vehicle will serve a community it has never visited. By stepping back from finished product design, the company creates space for distributed innovation.

The IMV Origin also signals a willingness to rethink what a vehicle manufacturer actually provides. Traditional automakers sell cars and trucks. Toyota, through this concept, proposes selling capability frameworks: mechanical systems and structural platforms that enable local economies to generate their own transportation solutions. The value proposition shifts from finished goods to enabling infrastructure. Whether this model scales into production remains to be seen, but the conceptual territory it explores challenges assumptions about how vehicles reach the people who need them.

Why the IMV Origin Acts as a Platform Rather Than a Product

What emerges from these choices is a rare form of restraint. By shipping a deliberately incomplete vehicle, Toyota acknowledges that the factory cannot know best, that distant engineers cannot anticipate the specific needs of a farming community in rural Africa or a delivery network in Southeast Asia. The concept trusts local fabricators to complete the design, trusts regional workshops to maintain and modify the platform, trusts communities to define what a truck should be in their specific context. This trust becomes a design decision as much as any chassis dimension or cab geometry.

The furniture shipping model, the open cab structure, the flatbed awaiting cargo solutions: all of these choices point toward a vehicle that exists as potential rather than product. As Koji Sato noted during the presentation, not finishing this vehicle was frustrating from a carmaker’s perspective, but not finishing it is what makes it a vehicle built for actual users, because people have different needs in their daily life and work. The IMV Origin does not try to be everything. It tries to be a starting point, a foundation, a system that gains identity through use and modification. Toyota builds the base. The world completes the truck.