There’s something deeply satisfying about watching designers take a swing at corporate boredom. Fevertime, a recent collaboration by Dugyeong Lee, Gyeong Wook Kim, MyeongHoon Cheon, and Dayong Yoon, does exactly that by transforming the typical video conference setup into something that looks like it belongs in a mid-80s arcade.

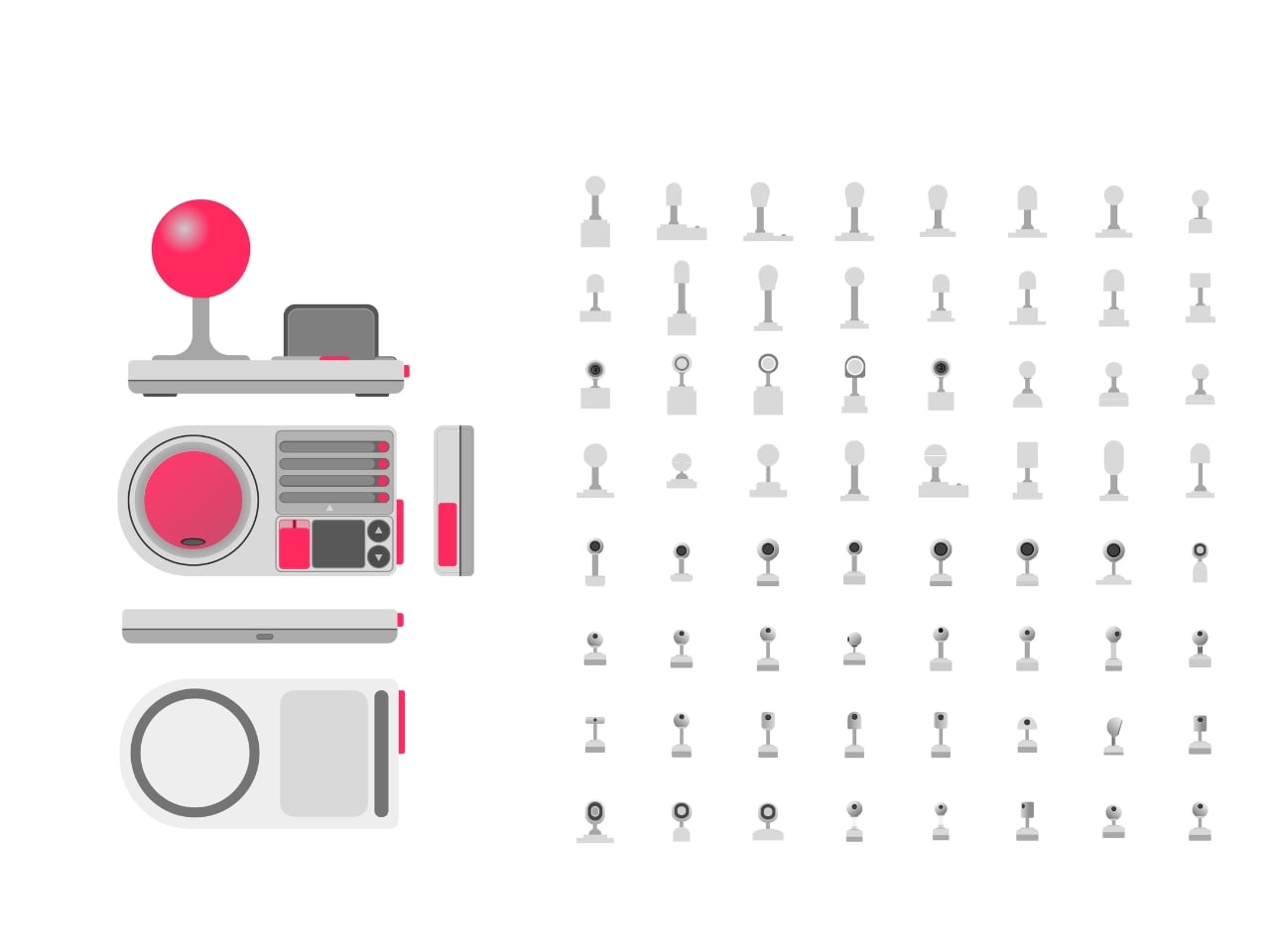

The concept is deceptively simple: what if meetings felt less like mandatory Zoom rectangles and more like gathering around a shared screen? The team created a physical meeting system inspired by retro game consoles, complete with a bright red spherical camera perched on a stand like some cheerful robot companion, and a base unit that wouldn’t look out of place next to your old Nintendo. There are even cartridge-style slots and that unmistakable game controller aesthetic, all rendered in a palette of scorched red, neon accents, and soft grays.

Designers: Dugyeong Lee, Gyeong Wook Kim, MyeongHoon Cheon, dayong Yoon

But this isn’t just nostalgia bait. The designers identified a real problem with modern collaboration tools: everyone staring at their own screens creates this weird isolation, even when you’re supposedly “together” in a virtual room. Fevertime flips that script by projecting content onto a shared surface, encouraging actual eye contact and spatial awareness. The physical device becomes a focal point, something to gather around rather than disappear behind.

The system lets users set up meetings in advance, defining time, participants, and structure before anyone logs on. When the session starts, participants can instantly share content from their personal devices onto the collective display. Everything stays synced and visible to everyone simultaneously. No more “Can you see my screen?” or fumbling through share settings while everyone waits. The interface shows meeting cards, schedules, and project data in a clean, modular layout that feels more like organizing a playlist than managing corporate logistics.

What makes Fevertime visually compelling is how committed it is to the gaming metaphor. The red sphere isn’t trying to look sleek or invisible like most tech hardware. It wants to be noticed. It practically begs to be the conversation starter in the room. The cartridge system for what appears to be different meeting modes or templates plays into that collectible, tactable quality that made physical media so satisfying. You’re not just clicking through digital menus; you’re handling objects, sliding things into slots, physically engaging with the technology.

The UI design carries that same energy. Bright pink highlight screens pop against neutral backgrounds. Typography is bold and condensed, channeling the space constraints of old arcade cabinets where every pixel counted. Cards and modules feel like game level selects or achievement screens. There’s a playful confidence in the branding, with the Fevertime logo rendered in that wavy, almost melting typography that suggests heat and intensity without being aggressive.

The designers describe the project as capturing “a single moment of high-intensity creative output,” that fever state when an idea finally clicks and everything flows. That philosophy shows up in the pulsing, breathing quality of the custom lettering, where font weights fluctuate to create visual rhythm. It’s design that refuses to sit still, much like the creative process it’s trying to facilitate.

From a product design perspective, Fevertime sits in that interesting space between speculative concept and plausible near-future tech. The physical components look production-ready, with thoughtful details like ventilation ridges on the base unit and a weighted stand for the camera sphere. But there’s also a conceptual boldness here, a willingness to say “what if meeting technology looked completely different from what we’re used to?”

The team used Adobe’s creative suite to develop the project, combining Photoshop and Illustrator for the identity work with After Effects for motion elements. That mix of static and animated content gives Fevertime a kinetic presence even in still images. You can imagine the interface cards sliding, the logo pulsing, the whole system humming with that arcade-ready energy.

Whether Fevertime ever makes it to market is almost beside the point. As a design exercise, it asks useful questions about how we physically and emotionally experience collaboration technology. It challenges the assumption that workplace tools need to look serious and minimal. And it demonstrates how pulling from gaming culture can make even something as mundane as meeting software feel fresh and approachable. Sometimes the best design projects are the ones that make you think, “Wait, why doesn’t everything look like this?”