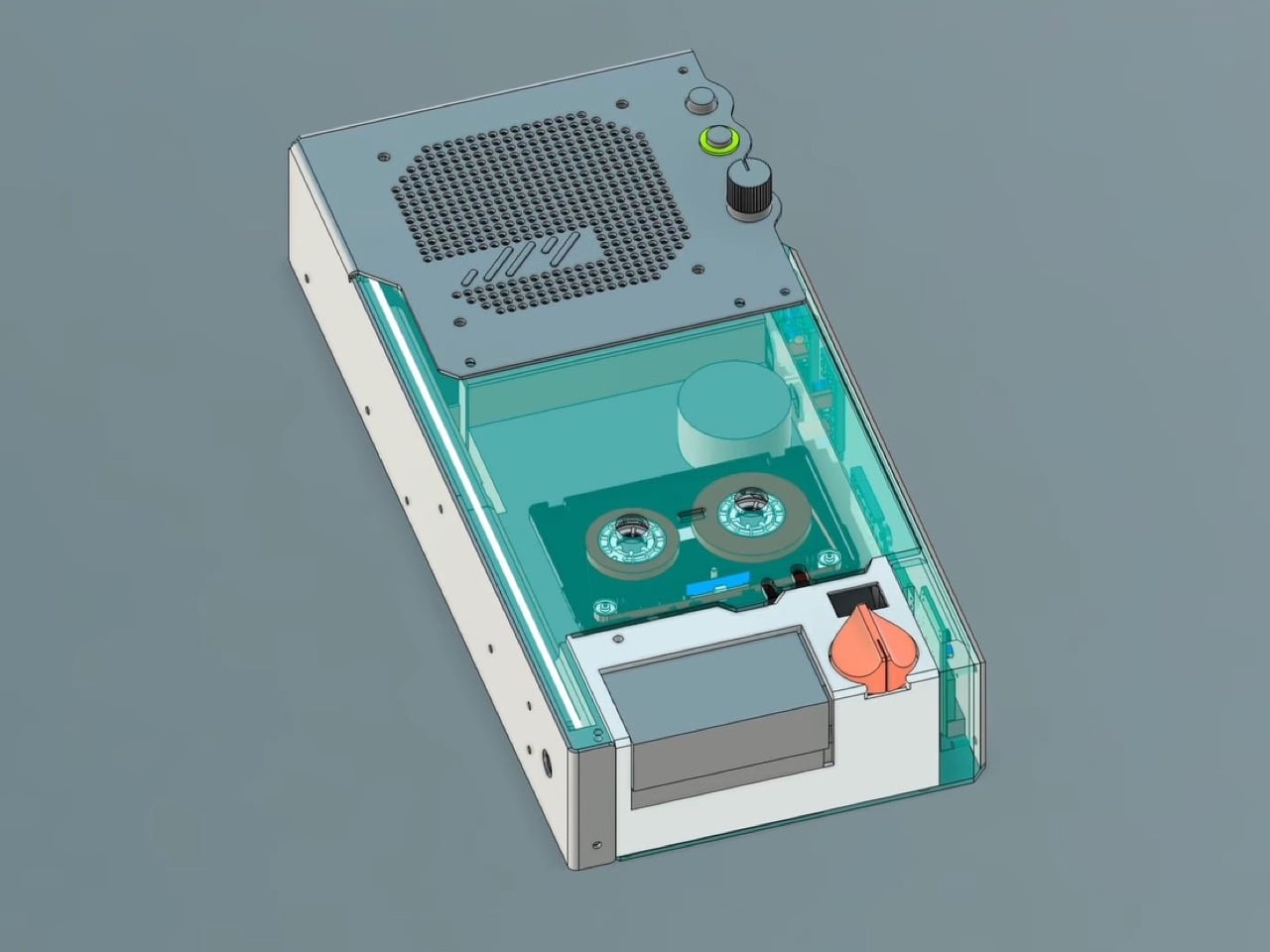

Most audio enthusiasts fall into one of two camps: the ones chasing perfect fidelity with lossless files and the ones who swear their vinyl sounds warmer. Julius decided to build a bridge between these worlds, and it looks like something Q would hand to James Bond if the mission involved a particularly groovy villain.

His cassette streaming device takes Bluetooth audio and runs it through an actual tape loop before playback, physically imprinting that analog character onto digital streams. The engineering journey was brutal. Turns out cassette decks from decades past have some deeply weird ideas about electrical grounding, and getting modern Bluetooth hardware to play nice with positive-rail-referenced vintage electronics required DC isolating voltage regulators and more than a few creative workarounds. The payoff is a device that looks incredible and introduces real tape saturation without any digital fakery.

Designer: Julius Makes

The concept is straightforward. Bluetooth audio arrives digitally, converts to analog, mixes from stereo to mono, records onto cassette tape, travels around the loop, hits a playback head, then reaches the speaker. That physical trip through magnetic tape creates the warmth people obsess over. The compression happens because ferric oxide particles on polyester film genuinely can’t capture digital audio’s full range. These are real physical limitations making the sound different, and somehow our ears prefer it that way. Julius made the tape loop visible on purpose, sitting outside the cassette with orange guide brackets so you watch it move while listening.

Getting everything to work required solving problems that shouldn’t exist anymore. Cassette decks connect their chassis to the positive power rail instead of ground. Julius only learned this after bolting his grounded metal case directly to the deck with screws, nearly shorting everything. The audio input shielding also runs to positive, which makes zero sense if you’re used to modern electronics. His Bluetooth module expected normal ground references, creating a fundamental incompatibility. An isolation transformer from AliExpress failed completely. He tried powering the Bluetooth at 12.5 volts while referencing it to 7.5 volts, but that rail wouldn’t sink current. Three months of debugging until DC isolating voltage regulators finally solved it.

The VU meter uses a fluorescent tube that works backward from what you’d expect. Silence keeps it fully lit, loud beats make it dim. Julius inverts the signal on purpose so the tube glows when the device sits idle, which looks better and extends the tube’s life. The circuit gains the audio signal 500 times, clips it hard to isolate peaks, then runs through a diode detector with a capacitor for smoothing. The power amp inverts everything again and boosts another five times to drive the tube. The lag you see in the meter’s response comes from that smoothing capacitor, which is a feature since nobody wants a seizure-inducing flicker.

He built five separate circuit modules. One auto-starts the Bluetooth by faking a long button press with an RC pulse generator. Another converts stereo to mono for the recorder. The playback preamp amplifies the tape signal and applies EQ compensation, splitting output between the speaker and the meter circuits. Everything lives on custom PCBs he designed in KiCad after a month of learning the software. The stainless steel case handles shielding and heat dissipation from the power amp. A laser-cut acrylic panel makes the front transparent. The big orange knob pushes record volume into distortion territory. The small knob controls speaker output. Input and output jacks mean you can use this as a tape delay or saturation processor for other gear, which honestly might be more useful than Bluetooth streaming through cassette tape. But useful was never really the point.