There’s a particular kind of quiet that settles after a wildfire. Not peaceful, not comfortable, just a heavy stillness where something used to be. In January 2025, the Eaton Fire burned through Altadena in the foothills of Los Angeles for twenty-five days, taking nineteen lives and destroying more than 9,000 structures. It became the second most destructive wildfire in California history, leaving behind charred earth and the skeletal remains of trees that once shaded neighborhoods and backyards.

A year later, at Marta gallery in Los Angeles, 22 local artists and designers are doing something quietly radical with what’s left. The exhibition “From the Upper Valley in the Foothills” transforms salvaged wood from those burned Altadena trees into chairs, stools, benches, bowls, and other functional objects. Curated by sculptor Vince Skelly with material support from Angel City Lumber, the show runs through January 31st and offers a different kind of memorial.

Designer: Vince Skelly (curator)

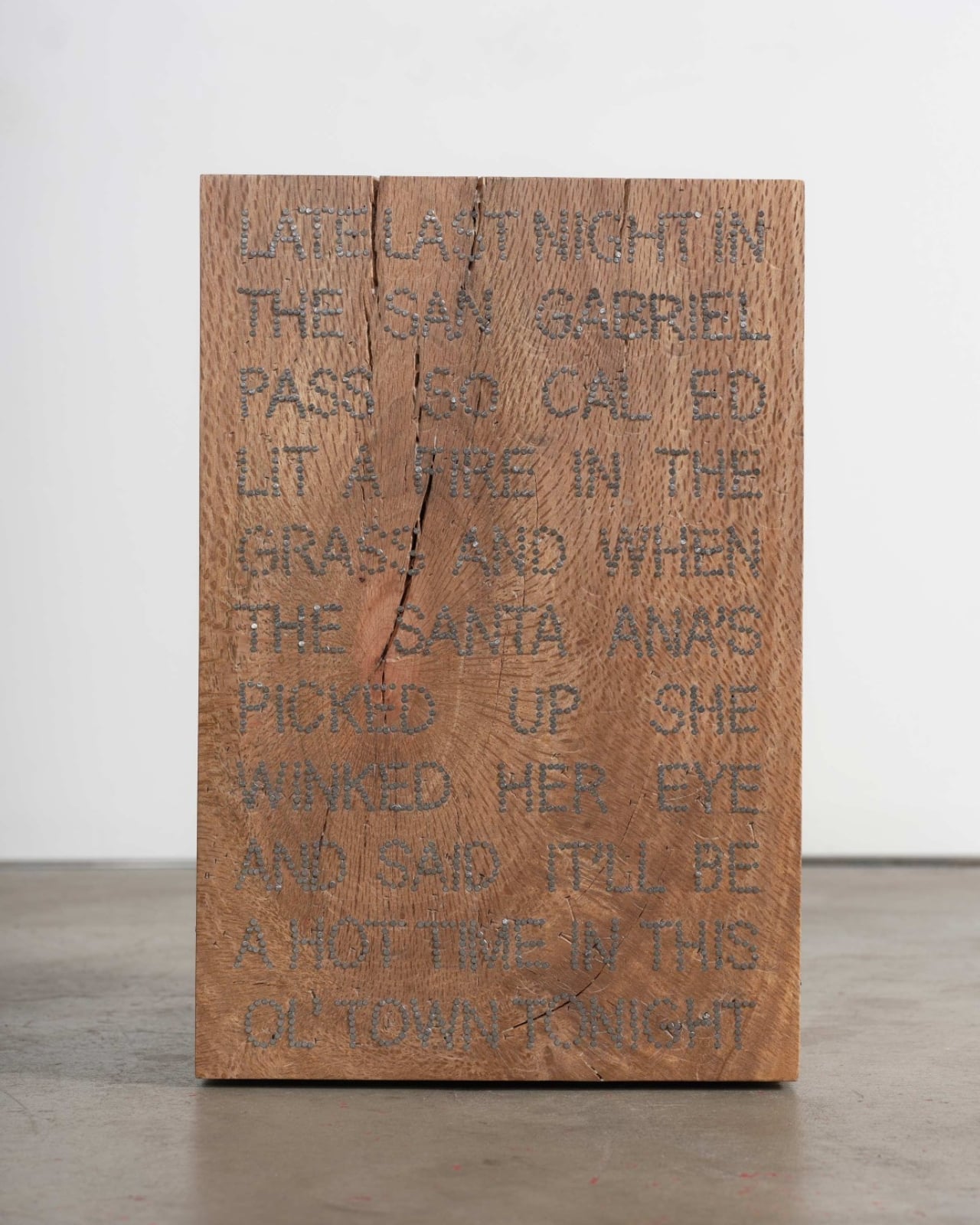

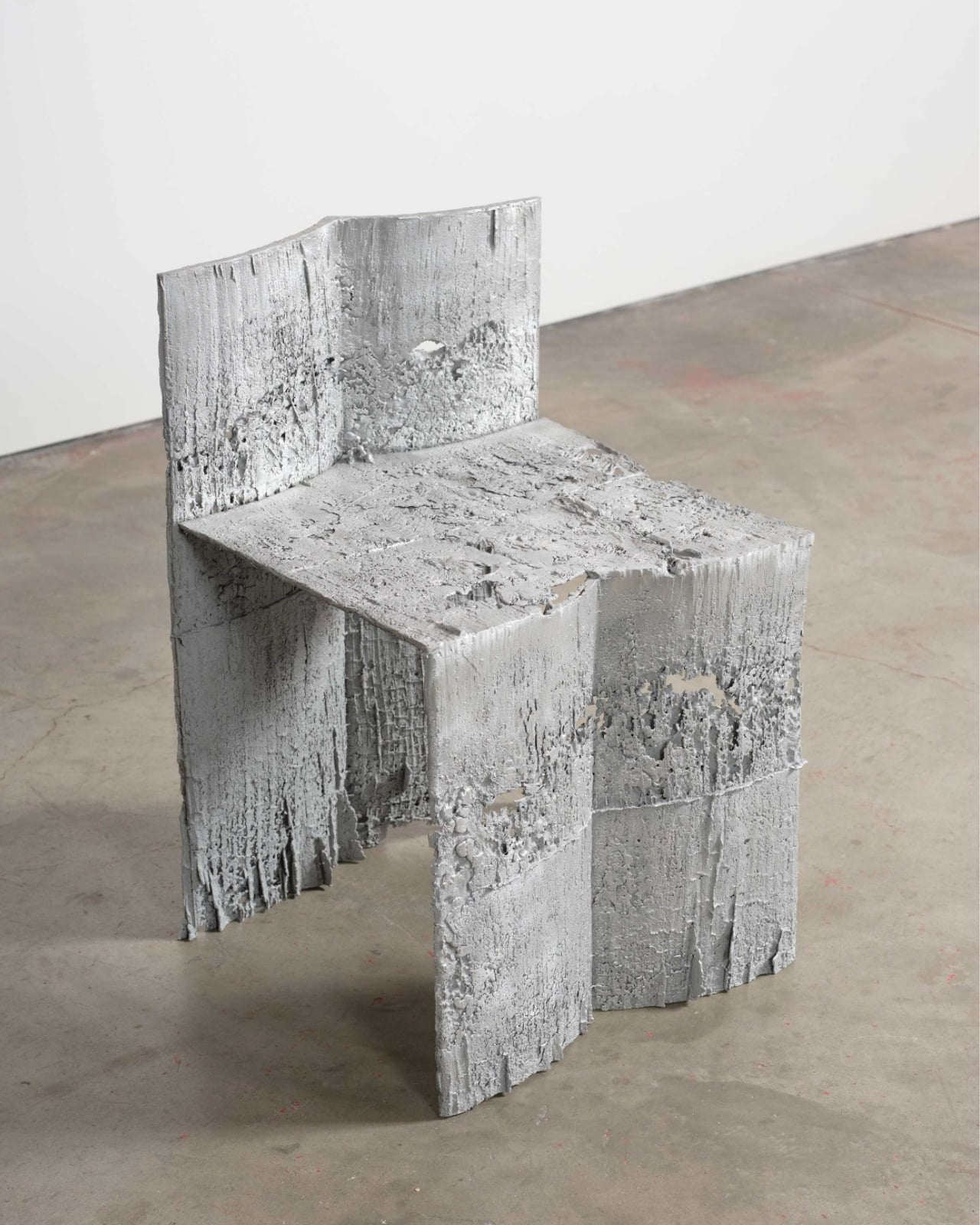

This isn’t your typical tribute. There are no plaques, no somber photographs, no distance between you and the disaster. Instead, you’re invited to sit on it, hold it, contemplate it. The wood itself, sourced from species like Aleppo pine, cedar, coastal live oak, and shamel ash, carries visible traces of fire damage, smoke marks, and irregular grain patterns. Each piece holds a kind of double existence: both the tree it was and the home it might have shaded.

Skelly wanted the exhibition to feel like a true community response, so he focused on local designers and artists who each had their own experiences with the fires. The resulting collection is remarkably varied. Some pieces lean sculptural and contemplative, others embrace pure functionality. There’s Doug McCollough’s decorative bowl, Tristan Louis Marsh’s floral stool, and Base 10’s Watari bench, each handling the material’s history differently.

What makes this work compelling is the tension between destruction and creation. Angel City Lumber, a local mill that sources downed trees for community projects, collected the wood cleared from Altadena after the fire. By transforming debris into design objects, the exhibition reframes devastation not as an ending but as an uncomfortable, complicated beginning. The burned wood becomes a vessel for memory, loss, and whatever regeneration might look like.

Function here isn’t just practical. It’s conceptual. These chairs and benches aren’t simply places to rest, they’re propositions about how devastated spaces might once again support everyday life. The act of sitting on a stool made from fire-damaged oak becomes a small gesture of reclamation, a way of saying that what was lost can still hold weight, still serve a purpose, still matter.

The exhibition also raises quieter questions about the role of artists and designers during climate instability. Is it enough to make beautiful objects from catastrophe? Does craft honor the loss or aestheticize it? The show doesn’t offer easy answers, but it does suggest that making something useful from what remains is its own kind of resistance. There’s dignity in refusing to let devastation be the final word.

Marta’s presentation feels particularly resonant because it acknowledges that these objects are meant to be touched and experienced, just like the forests they come from. In an era when wildfires are becoming annual events and California’s landscape is increasingly defined by cycles of burning and rebuilding, this direct engagement feels necessary. The wood doesn’t let you forget what happened, but it also doesn’t let you look away.

What stays with you after visiting “From the Upper Valley in the Foothills” isn’t any single piece but the cumulative effect of seeing 22 different responses to the same material. Each designer grappled with the same scarred wood and found their own way through it. Some leaned into the damage, others smoothed it away. Some made monuments, others made chairs. Together, they create a portrait of a community trying to process an event that reshaped not just the landscape but the psyche of an entire city.

The exhibition is both memorial and workshop, grief and pragmatism sitting side by side. It suggests that sometimes the best way to honor what’s lost is to build something from the wreckage, to take what the fire left behind and give it a second life. Not as a replacement for what was, but as a reminder that even in the aftermath, there’s still wood to work with, still hands to shape it, still a future that needs furniture.